current projects ︎ current projects ︎ current projects ︎ current projects

Pre-colombian Valdivia from the Alabado Museum in Quito, Ecuador

Pre-colombian Valdivia from the Alabado Museum in Quito, EcuadorFollow our journey through Ecuador’s geographies, the architectural research project entitled “Cañ and Ara: Mending Climates with Vernacular Cosmovisions,” generously selected by the Fulbright Program.

︎︎︎Visit our Blog HERE

Council listening intently to Kenao president Yadira Ocoguaje’s speech

Siekopai women from Siekoya Remolino, Ecuador, describe the innovations made within their women’s artist collective Kenao.

︎︎︎Learn how we are supporting Kenao HERE

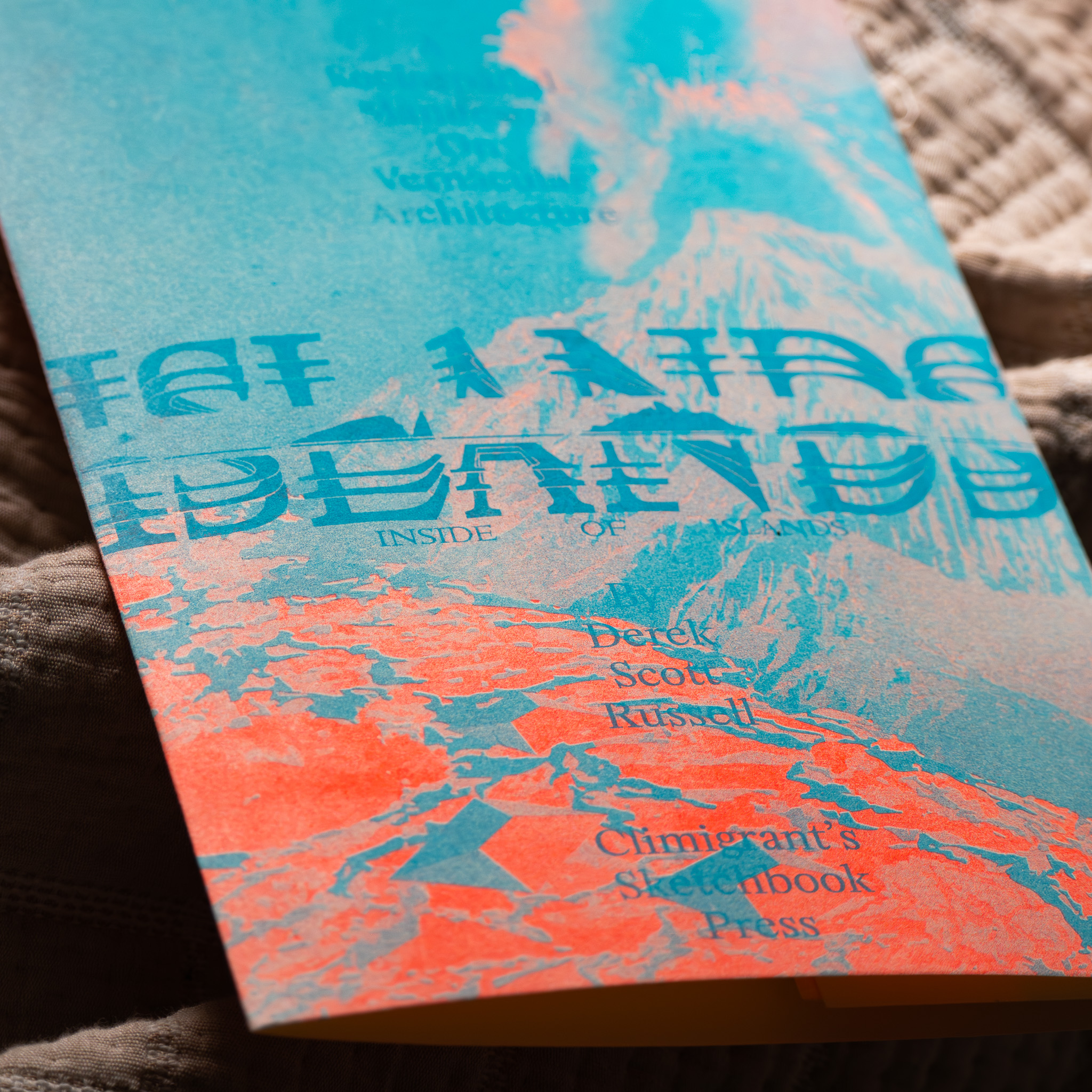

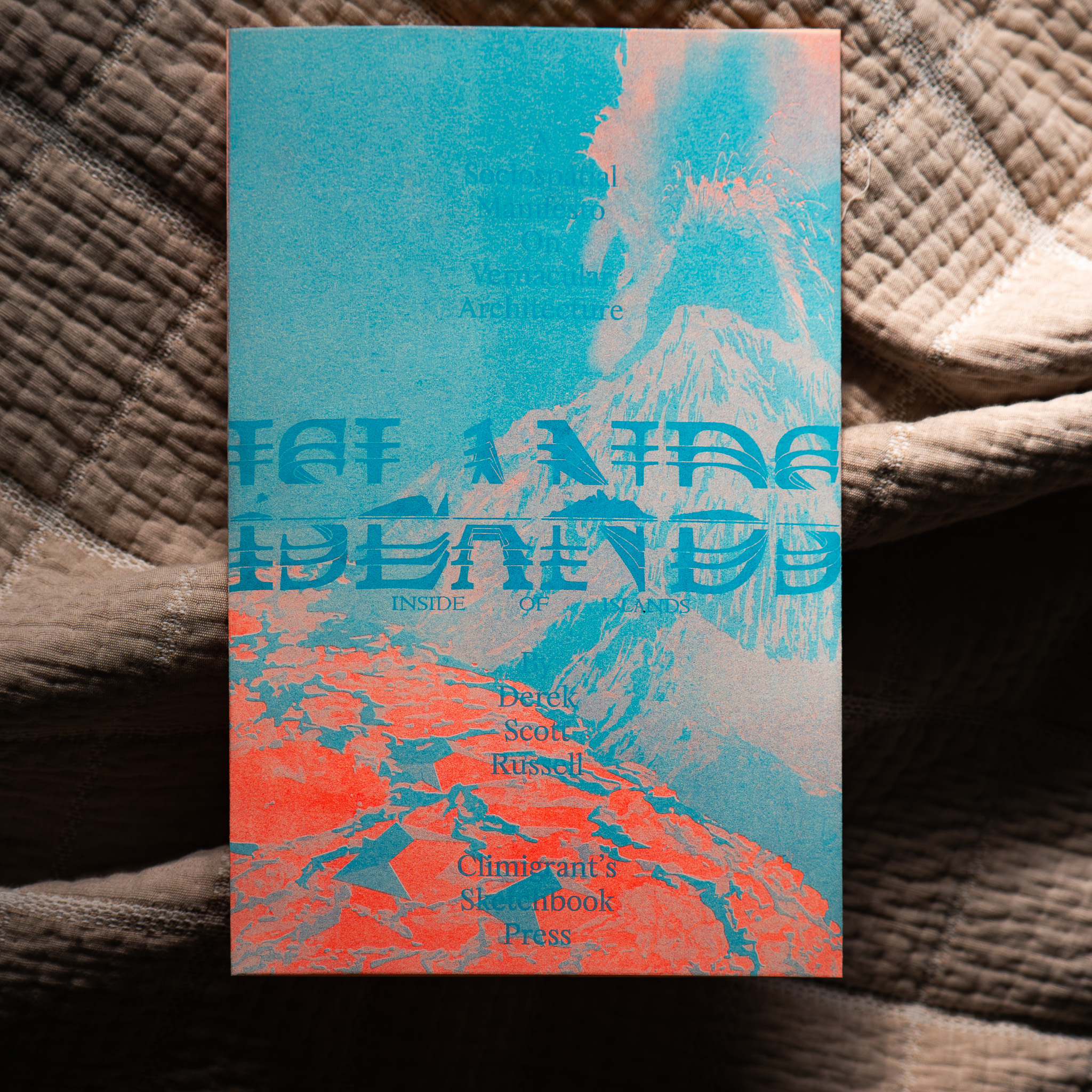

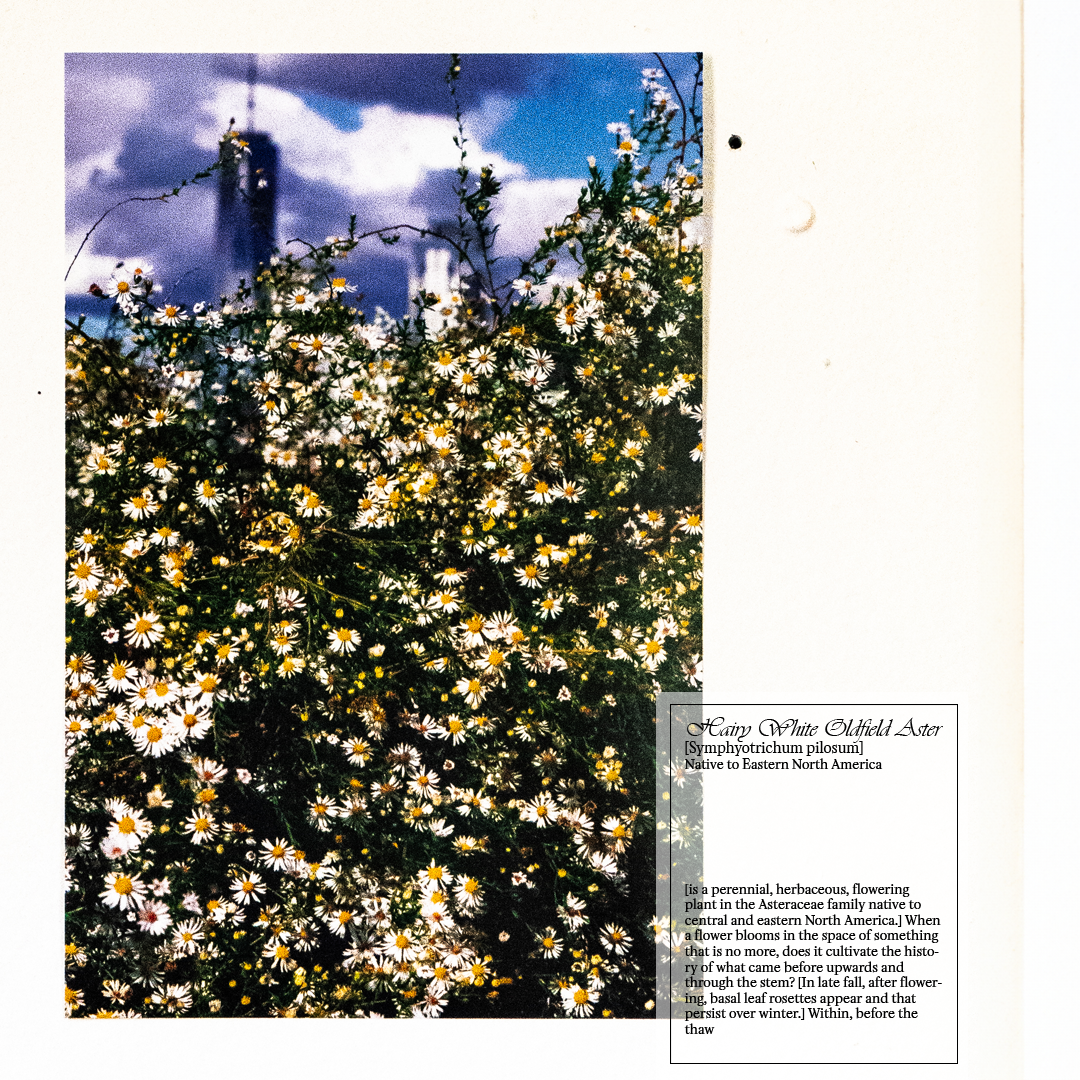

“Moth Season” in mnemotope 005, Bog Bodies Press

mnemotope is a community magazine by Bog Bodies Press, derived from a term that’s used in writings about archaeological finds. “a mnemotope is something (often historical) that compresses the viewer’s experience of time; allowing them to be in the period in which the object came to be, at the site when it was excavated and in the museum looking at it.”

︎︎︎Learn how to read “Moth Season” and “Smokey Bear” HERE

︎ Find us on Instagram for more exclusive content

Still from short film “The Gods of Stone are Watching”

“The Gods of Stone are Watching,” short film and official selection of the exhibition Re-Examining Conservation at the Granoff Center for the Creative Arts, is now streaming on Vimeo.

︎︎︎Watch our short film HERE

Modern facsimile of Puebloan pottery emulating cacti, ironically as an artificial vessel for non-native succulents.

“Sere Beauty [Annotated]: Local Meditations, Counternarratives,” has been recently peer-reviewed by the Journal for Cultural Geography.

︎︎︎Learn how to read “Sere Beauty [Annotated]” HERE

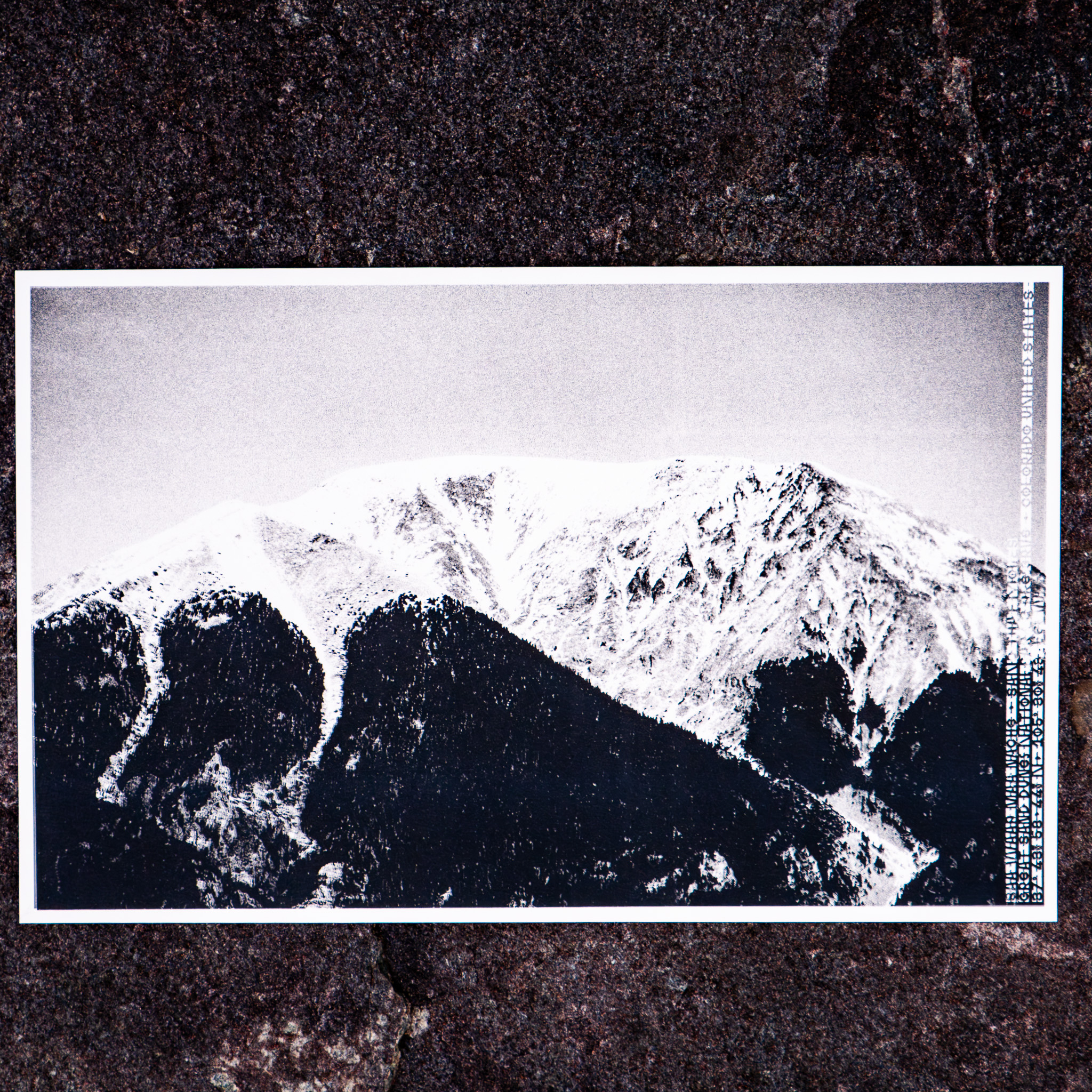

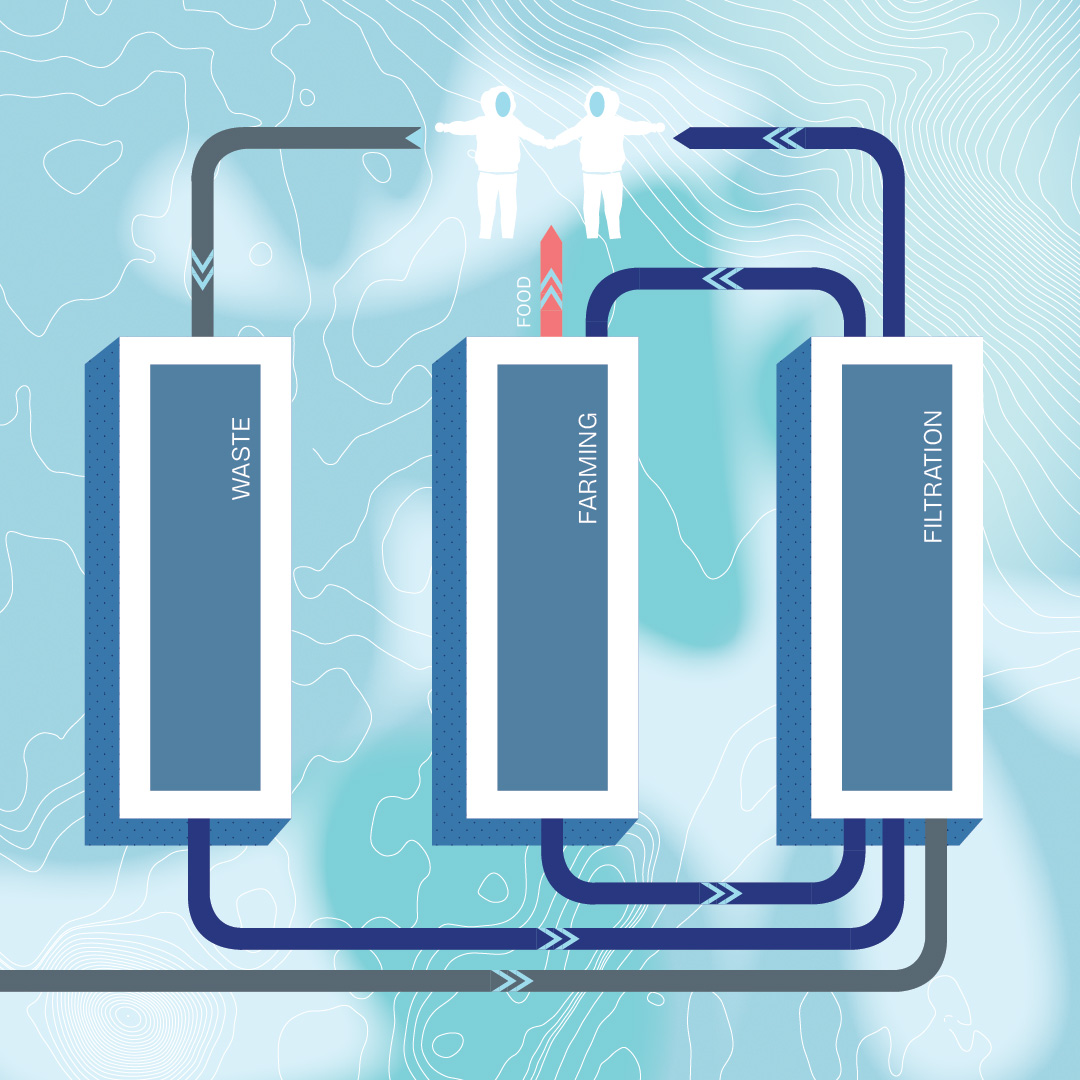

Still from Milanote archive of Open-Source research on Alaskan Sea Level Rise

“Alaska Research Archive,” captures documents and notes from a year-long collaboration with Sofie Kusaba investigating the impacts of Sea Level Rise on migration.

︎︎︎Peruse the archive HERE

speculations ︎ speculations ︎ speculations ︎ speculations

(Contra)Postcards

(Contra)Postcards09.2023 - ongoing

Bristlecones (Story Circle)

09.2021 - ongoing

Paper Wasps - Zine

04.2023